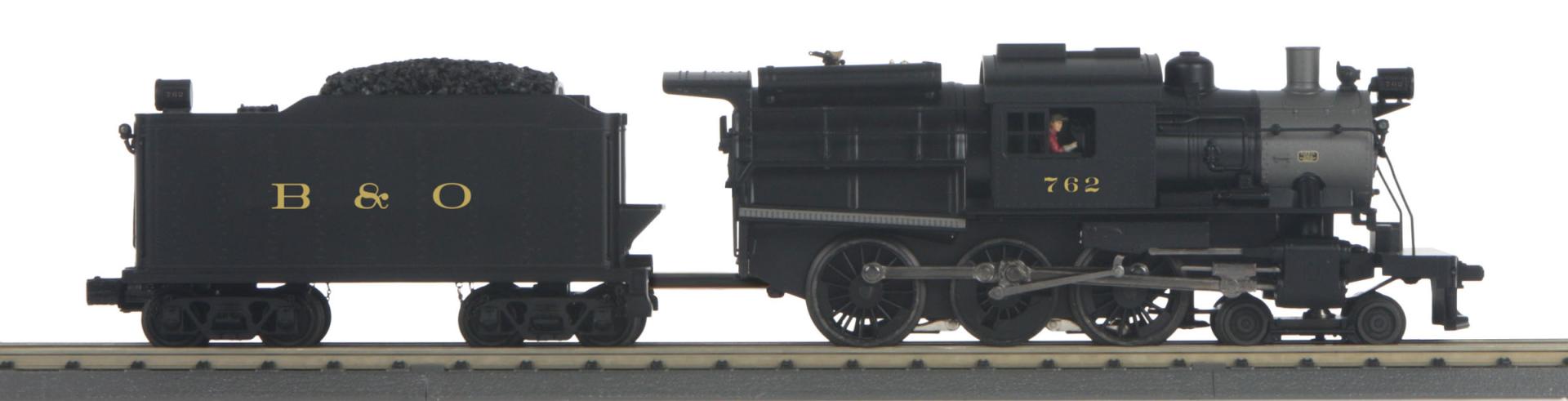

Baltimore & Ohio 4-6-0 Imperial Camelback Steam Engine w/Proto-Sound 3.0

Overview

Coal is coal, right? Not exactly. Early steam engines burned wood in part because the common coal of the time, rockhard anthracite, burned too slow for use in locomotives. The discovery of vast reserves of softer, faster-burning bituminous coal in the mid-1800s began the switch to coal as American's primary locomotive fuel. Anthracite, meanwhile, which burns with a smaller flame and little smoke, gained widespread use for home heating.

But one characteristic of anthracite mining was that close to 20% of production wound up as finely-ground, low quality waste, or culm, that accumulated in huge heaps outside the mines. In the 1870s, John E. Wooten of the Philadelphia & Reading Rail Road determined to explore the potential of culm as a cheap locomotive fuel. The result was the Wooten firebox, based on a large grate, or firebox floor, two to three times the size of a conventional grate and burning culm in a very thin layer. Whereas most engines of the time had a narrow firebox placed between the rear drivers, the Wooten firebox extended out over the drivers and was as wide as clearances allowed.

This, of course, made space in the cab rather tight, and designers soon moved the cab forward and placed it over the boiler barrel, which was smaller in diameter than the Wooten firebox. The result was the "Mother Hubbard" or Camelback (a reference to the odd bulge of its center cab) style of locomotive, with the engineer in the cab and the fireman back on the tender deck shoveling culm into the rear of the engine. By the late 1800s more than 40 roads rostered Mother Hubbards; among the largest users were the New York Ontario & Western, the Jersey Central, and its parent the Reading.

British author Brian Reed noted in Locomotives in Profile that "Firing a Mother Hubbard was no kind of job at all. The fireman was alone, and he had almost no range of vision. He could see the driving cab and the line ahead only if he hung well out sideways, and . it was difficult for him to determine if there was anything wrong in the cab." The engineer didn't have it much better. He was squeezed up against the hot boiler with the controls alongside him, rather than spread across the backhead as on a normal steamer. "Side rods breaking beneath his feet were even more disastrous than a fracture in a normal engine, and there was much less chance of living to tell the tale." No wonder that safety concerns led the Interstate Commerce Commission to ban the construction of new Mother Hubbards in 1918. Although not a favorite of crews, however, many proved to be remarkably long-lived workhorses, serving as fast freight and later as commuter engines until the end of steam.

Did You Know?

Camelbacks' fireboxes are wider and shallower to allow anthracite coal to burn hot.

Features

- Die-Cast Boiler and Chassis

- Die-Cast Tender Body

- Authentic Paint Scheme

- Real Coal Load in Tender

- Die-Cast Locomotive and Tender Trucks

- Engineer and Fireman Figures

- Metal Handrails and Bell

- Metal Wheels and Axles

- Remote Controlled Proto-Coupler

- Prototypical Rule 17 Lighting

- Constant Voltage Headlight

- Tender Truck Safety Chains

- Tender Backup Light

- LED-Illuminated Engine Class Lights and Tender Marker Lights

- Separately Added Metal Grab Irons

- Legible Builder's Plates

- Cab Interior Light

- Painted Cab Backhead Gauges

- Precision Flywheel-Equipped Motor

- Synchronized Puffing ProtoSmoke System

- Locomotive Speed Control In Scale MPH Increments

- Wireless Drawbar

- Onboard DCC Receiver

- Proto-Sound 3.0 With The Digital Command System Featuring: Passenger Station Proto-Effects

- Unit Measures:18" x 2 1/2" x 4"

- Operates On O-31 Curves Steam DCC Features

- Headlight/Tail light

- Bell

- Whistle

- Start-up/Shut-down

- Passenger Station/Freight Yard Sounds

- All Other Lights (On/Off)

- Master Volume

- Front Coupler

- Rear Coupler

- Forward Signal

- Reverse Signal

- Grade Crossing

- Smoke On/Off

- Smoke Volume

- Idle Sequence 3

- Idle Sequence 2

- Idle Sequence 1

- Extended Start-up

- Extended Shut-down

- One Shot Doppler

- Coupler Slack

- Coupler Close

- Single Horn Blast

- Engine Sounds

- Brake Sounds

- Cab Chatter

- Feature Reset

- Labor Chuff

- Drift Chuff